Hike-Use fork design process

High quality steel forks are not especially popular these days. They cannot compete with carbon fiber in weight, aerodynamics or theoretical strength, and depending on the case, not even in price. The advantages steel forks do have (if designed correctly) are reliability, safety, comfort, and, depending on the taste of the cyclist, style.

Steel is strong for its volume, meaning it can be made into slender tubes. It is easily worked so it can be bent elegantly. If it fails, it fails slowly, not suddenly, meaning reliability and safety. Carbon is easy to make in series, but almost impossible to make in small batches, which easily leads to geometrical or stylistical compromises.

These are all reasons why we absolutely wanted the Hike-Use to have a steel fork. We wanted it to be simple but beautiful and to make it as thin and thus flexible as practically possible to add comfort to the front of the bike. We also wanted the forks to get stiffer progressively when going to bigger sizes, just like our frames do.

All this meant a lot of planning, thinking and prototyping. Those that have followed our newsletter since the beginning already know that we had some, one could even say major, issues with the design of the front fork, mainly with the mandatory EN ISO stress and fatigue testing. Now that they’re solved, it all is OK, but seeing the pile of cracked and bent test forks brings out some stressful memories…

The testing process

A note to any competing bike brand designing a crown-style steel front fork, in case you find useful information in this article, and manage to EN ISO test your forks successfully on the first try thanks to said information, at least buy us a beer. Basically we have shared all the necessary clues by now in the newsletters, so our business secrets are leaked, so might as well present them clearly.

All of the frame and fork testing was done at the Zedler Institut in Germany. The frames themselves had no issues and passed on the first try. The fork tests performed on different versions were slightly different, so we don’t have an absolutely 100% clear picture of the facts, but this is our analysis:

The first model we tried was a thin-blade (small outer diameter) Columbus Cromor “rando extra long tip”, with the Pacenti Paris-Brest fork crown. This one passed the first 10,000 repeats of back-and-forth stress -stage of the EN ISO test, but in the “Zedler Advanced” test (which is more demanding than the basic test), with the same test method but higher force, the blades developed cracks next to the fork crown. We thought this was due to the crown’s design, but that may not be true. The crown probably is not optimal for stress risers, but the “better” crown developed similar cracks, though at more demanding loads.

The next ones we tried were the same Cromor blade with a different crown. These passed the first stages, and continued with the base test, not with the advanced test. These ones bent massively in the middle of the blades in the EN ISO “Static brake torque” test.

Then we tried a slightly larger tip diameter Reynolds 525 fork blade with the newer crown, and it also bent massively in the same brake test.

The first fork blades were extra thin and special, so it wasn’t a huge surprise that they didn’t pass. But the second one was a rather standard “road” fork blade, though raked a little more than most forks are (65mm vs 45mm).

So at this point we needed to take a different approach. We emailed Reynolds about the matter and ended up ordering heat treated 853 fork blades for the next test forks. The material's much higher strength should help specifically in the bending (cold-setting) that was happening in the brake torque test.

But as 853 needs to be bent before the heat-treatment, it needed to be a special order from Reynolds, and they took some time figuring out how to get the needed rake with the requested radius bend et cetera. This also meant that we had invested in a custom fork raking mold for Fort’s fork bender for nothing, as Reynolds had to use their own anyhow. We had even sent a 1950s French 650b fork to Fort as a reference. The raking mold didn’t cost much compared to the testing process in general though.

After some issues with the raking and waiting around for some months, the new fork blades were finally done and shipped to Fort. Every time we needed a new set of test forks, Fort provided them quickly, but as they were single pieces, not a series of forks, we of course had to pay extra to get them done. Later this also meant that the delivery of the framesets was delayed for multiple months, as we had to wait for Reynolds to make the final batch of fork blades.

Memories of restless nights and painful test reports and wastes of money still haunt us when looking back to this time, and it wasn’t fun waiting around for the final report. But our skin had also thickened by then, and, well, it just had to be done, no way around it.

And then some beautiful sunny day, or was it cloudy or rainy, the test report arrived with the hallowed marking of “OK” for the DIN EN ISO 4210:2023-05 test protocol! Both for the 584 and 622 fork models. The forks were still mangled and cracked, but only after the final and most harsh impact tests.

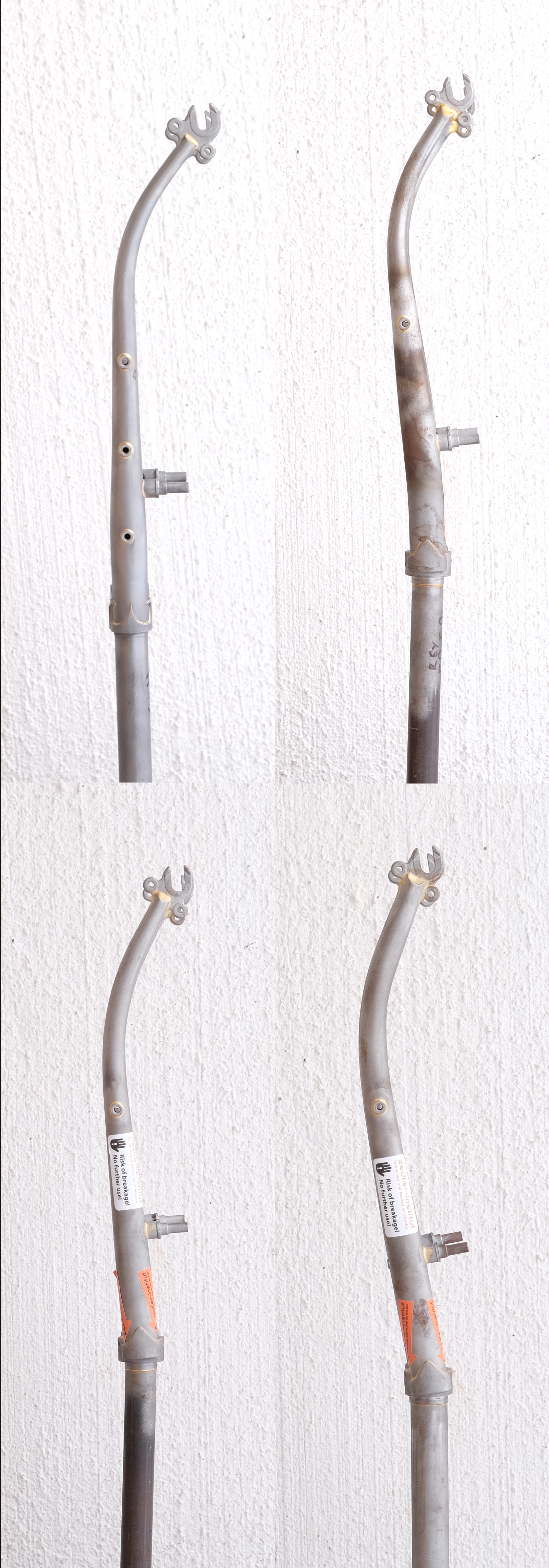

Clockwise from top left: 1. Columbus cromor first version with pacenti crown (this one is a non-tested sample), 2. Reynolds 525, blade bent in “brake test”, 3. Reynolds 853 road. This one has passed the test and only cracked and bent in the final “full-on crash” test. 4. Reynolds 853 disc. Also passed the test and bent and cracked in the final phase.

Fork design - materials and size

This is how the final production model test-passed forks are like:

The axle-to-crown distance is 363mm for 559 (size 53), 375mm for 584 (sizes 55,57,59) and 395mm for 622 forks (sizes 61,63,65). The rake is 65mm on all models.

The 559 and 584 size forks use a “road” spec Reynolds 853 fork blade, rather standard 27,5x20mm oval into a 13mm tip. The wall thickness in the raw tube is 1,0mm near the crown and thins out to 0,6 near the dropout. Due to the tapering of the fork blade (making the diameter thin out towards the bottom), which “condenses” the raw tube, the wall thickness is more constant in the final product.

The 622 forks use a disc brake -spec Reynolds 853 blade, which is significantly bigger and stiffer in its lower half. The “road” spec blade is too short to be used in the taller forks, and anyhow we wanted the fork stiffness to increase in the bigger sizes, whereas using the same blade for a taller fork would have caused the opposite to be true. (A longer tube is more flexible)

The upper half is basically the same, only the wall thickness is a tiny bit thicker at 1,1mm. The tip is 17,2mm in diameter, meaning it's much bigger and thus stiffer than the smaller forks, even as the fork gets longer. Especially for the biggest riders it’s probably mostly a good thing. It’s still not more stiff than your average disc brake fork. (At least Surly used similar spec fork blades even on the rim-brake forks, when they still made those) The compromise here is that for light weight riders on larger sizes (61 and up), they will not have an especially thin-blade flexible fork, like the people on the smaller sizes.

The original prototype forks with the Cromor super thin blades have the lower 13mm diameter section extending well into the curver portion, which should make it even more flexible and comfortable. But the little bit thicker outer diameter 853 fork blades of the production fork have a significantly thinner wall thickness in this portion, so some of that flex is gained back there.

The size progression, from left to right: 1. the super thin diameter Columbus Cromor “Rando extra long taper”, 2. the more normal Reynolds 525, 3. similar diameter as 525 but in super strong heat-treated Reynolds 853 road, 4. Visibly bigger and stronger Reynolds 853 disc. The last two are the approved production models.

Thoughts on testing

Like said, also the forks that passed the test did break, and it was that the crown itself bent and twisted backwards in the brake torque and impact tests. Possibly some super-strong fork crown would be even more durable, but then again we haven’t really seen any real world cases of crowns twisting… Neither have we seen or found on the internet forks that are bent halfway down the blade due to braking, which the earlier test forks did in the so-called braking test. How accurately the EN ISO test is simulating real world situations is hard to say.

All this also points to the fact that unicrown forks are probably generally a stronger design, which is the reason most steel mountain bikes (and gravel bikes) use that style. Their down-side is that mounting fenders neatly is more challenging, and it easily increases the A-C of the fork, whereas a crown frees up space in that tight area. And for (all)road use the crowned forks are plenty strong. Cast crowns are arguably also prettier.

All our problems and waste of money probably could have been avoided with the help of a smart engineer, or someone who has had similar experiences making steel forks. But the fact is there aren’t that many companies that are making lightweight steel forks in a non-custom setting anymore. To be honest, we didn’t think it to be that hard, and once we were in the middle of testing there was no way ahead but to try different versions.

The test laboratory Zedler Insitut, who could have had some information for us, unfortunately didn’t prove very helpful. Like they themselves said when we interviewed them mid-testing, almost no one is making steel forks in Europe, so they are not testing steel forks in Europe either. And the EN ISO tests are new-ish, so that in the era of classic steel bikes they were not yet around. It seems that completely normal old steel road forks would not pass the test, but as far as we know they have a very good track record of staying in one piece, or at least of failing in a safe manner. The latter of course is very important: forks should break by bending or cracking slowly (like steel forks usually do) not by suddenly breaking in half. (Which is the breakage behaviour of some other materials.) Maybe the test is too demanding, maybe it’s demanding in the wrong way, maybe it’s correct, who knows. In any case we had to pass the test to have a legal product in most EU countries.

Weight limits

The forks (and frames, which passed on first try), have an official weight limit of 100kg system weight. This is the weight that the EN ISO test is simulating and thus it is what we can officially say. We did try the 622 forks in the Advanced test, but they developed some cracks, again near the fork crown, and thus did not get the official system weight recommendation of 120 kgs that that test is simulating according to Zedler. So our own weight recommendations for the forks are 100kg total system weight for 559 and 584 models (sizes 53,55,57,59) and 110kg system weight for the 622 models (sizes 61,63,65). Weights inside these limits in the use case of “city & trekking”, which basically means no jumping or trail riding, are considered to be under our warranty.

The conclusions

Most manufacturers, both historically and in the present day, share quite little information about their products. And even when the frame tubeset being used is published, the fork is most often forgotten. It is quite surprising how hard it is to find any thorough information on steel fork design. We had to measure and research different types of forks in older and newer bikes, comparing those used in road, track, touring, MTB and gravel bicycles. The thinnest we found were on a 1968 Jo Routens 700c randonneuse, and the largest ones on a Stooge Rambler, which totally makes sense, they are made for exactly opposite use cases.

Of course the offerings of the tube manufacturers, in our case Reynolds and Columbus, also limit the choice and not every theoretical design is easily put into actual production.

We could have looked into ever more options more tests, but as we have noted, old steel forks work well and don’t suddenly explode, and also our first super thin non-heat-treated-steel prototype forks have worked well even in various warranty-xtremely-void-MTB-type scenarios, and with around 15,000km of continued general use with no issues. So we consider the ones we now have perfectly fine or even excellent for their intended use. We had an ambitious goal for the fork design, which was achieved. In the end we are thousands of euros poorer but we do have a qualified product that we are very happy with. And of course learning is priceless.